Tuesday, 10 November 2009

Lesson Learned: Don't Whistle in Damascus

My friend never arrived, though she called later on telling me that she had found a place with another helpful Iranian near the Zaynabiyya shrine. I sat on the steps of Bab Touma for a good half hour after that, dizzy with adrenaline, my hands shaking and my forehead dotted with beads of cold sweat. For a moment I was overcome by a desire to leave this country immediately and forever. Then I thought about all those delicious pomegranates...

Sunday, 8 November 2009

A day in Konya

It's hard to describe an encounter with a man who has brought so much to my life. Standing before Mowlana Rumi shattered any pretensions I harbored about having recovered from the romanticism that afflicts so many from my country. A twelve hour night bus took me from Istanbul to Konya. I stepped off the bus, made my way in broken Turkish towards the tram station, and watched the streets of Konya pass me by as I fell deeper and deeper into thought. All the while every line I had ever learned made itself available to my tired thoughts...

beshno az ney, chon hekāyat mikonad...az jodā-ee-hā shekāyat mikonad...

Listen to the reed as it speaks, complaining of separation...

Chanting and stumbling, I walked from the tram station to the nearest restaurant. I hadn't eaten a square meal in what seemed like forever. Only after I entered I realized I was in a MacDonald's. The garish yellow-red interior snapped me out of my romantic daze. I ordered a MacDonald's hamburger for what would be the first time in my life. Underwhelmed by the reaching of yet another momentous benchmark, I finished my meal down to the last perfectly manicured fry and made my way to the shrine.

I walked past the city garden, past mosque after ancient mosque, castles and forts and history that was so common in Turkey I had gotten used to seeing it all sort of lying around. I walked past the Mowlana restaurant, the Mowlana hotel, the Mowlana bank and coffee shop selling Mowlana coffee at prices Mowlana would never be able to afford, past ten thousand little figurines of whirling darvishes, and clock faces of whirling darvishes and signs for two for one deals on whirling darvishes....

At long last, I saw the turquoise dome of the shrine emerging from behind the trees. And then, I did what every self respecting Persian gentleman does in the face of the numinous; I sat myself down and cried big, hot tears, unfazed by the stares of passers by. I walked on, past the jinazah prayer at the masjid to my left, past the ticket booth swarming with pilgrims turned tourists and past the rubble of "renovation" work. Two liras later I was inside the "Mevlana Museum", determined to at least try containing myself. The museum was packed like a bazaar with all of Mowlana's purported stuff, but my watery eyes were fixed on a few simple lines, written in nasta'liq on the far wall...

bāzā, bāzā, harānche hasti, bāzā

gar kāfar-o bot parasti, bāzā

in dargah,dargah-e nā-omeedee neest

sad bār agar towbe shekasti, bāzā

Return, return, whatever you are

if you are kafer or idolater, return

for this house is not the house of hopelessness

If you broke your towbas a hundred times, return...

More tears, more wandering, more encounters with beautiful, warm, friendly Konyans inviting me into their lives without reservation, more tea and shopping later, I was on another bus, heading back to Syria.

Thursday, 8 October 2009

Thursday, 1 October 2009

Grammar is not a game!

I was far too captivated by the professor's rapid fire fus'ha to notice the melodramatic aside. He whisked us through the next two hours, I and nearly three hundred freshmen on the edge of our Ottoman era benches. Professor Yusuf threw us stanza after classical stanza, manipulated verses like a magician, an inveritable Gandalf of Grammar, "Is the poet al-Jareer telling us that every heart seeks its beloved, or is he telling us something more, about his own heart in particular. thi'qalbin, is it what it seems, or is thi really short of hathihi?!"

Some, unable to contain themselves, would shout out answers, flail their arms and rise from their seats. All of this went against the almost nineteenth century rules governing teacher student etiquette at Damascus University. "We are an in an adab department after all, let us conduct ourselves with adab," he said, playing on the dual meaning of adab as both grammar and manners. Smiling, Professor Yusuf assured students there would be ample time in the coming classes for outbursts of morphological enthusiasm. Hijabs glittered under the auditorium lights, pens scratched furiously trying to keep up, and the professor soldiered on.

Clearly in over my head, I nevertheless knew I had come to the right place. Language institutes for foreigners? Not I! Hanif al-Batuta, fresh from Bengal, will sit in a Syrian class with Syrian students. And before I realized how desperately behind I was falling, my mind was already dancing with thoughts of those early Persian linguists, to Sibawayh, who composed an elaborate and precise Arabic grammar as early as the 8th century...

I walked out of class, my mind awash with classical Arabic. As for the bemused expression on the face of the roadside fruit vendor, I only realized after the fact that I had asked him something that roughly approximated to, "When, pray, shall yonder bus arrive at this here spot where we are currently standing."

Sunday, 20 September 2009

Damascus

Raifeh has been living and renting out apartments to foreigners like me in Bab Touma since long before I was born. The years haven't been particularly kind to her. At about sixty, she walks with a visible hunch, the product of a difficult life in rural Sueda. Somehow, though, when she smiles through her sun baked wrinkles, fires up another cigarette, or helps her unimaginably old mother to bed, it becomes easier to picture a vibrant Raifeh's better days.

Last night, after the show, over another round of coffee, in a thick as soup Syrian dialect, Madame Raifeh decided to tell me a story.

"In Sueda, there were no cars, no electricity, no doctors." Drought, she said, had hit the mostly Christian and Druze village for nearly ten years to the dismay of her farmer father. Each day, her mother would walk about two hours to a river, collect enough drinking water for the family, and walk back. I tried to picture Madame Raifeh's mother, quietly sleeping on the sofa, with an urn full of water on her tired shoulders. Schools had just become a part of Suedan life, and a six year old Raifeh was eager to attend. She would, of course, have to bring along her younger sister, with whom she'd share the single pen her father had bought them. Raifeh and her sister would take turns using the pen to finish their assignments.

"And so one day, my sister told me she was sick and didn't want to come to school. This made me happy because I would have the pen all to myself. I was little, I couldn't understand what sickness was. I returned home and asked my sister if she wanted to finish her assignment. Again, she said no, that she was feeling sick, complaining about a pain in her stomach. Without giving it a second thought, I ran off and played with my friends. A few hours later, my sister had died from an infected appendix. Well of course she died, there was no doctor, no medicine or anything! I was bit happy after that, too. All I could understand in my six year old mind was that I would get all of my little sister's old things. That's so sad, right?"

Madame Raifeh said all this with a bubbly, storytelling kind of cheer. And so it was. I finished my coffee, bid Raifeh good night, and took another long walk through old Damascus.

Saturday, 18 July 2009

How do you feel about Catfish?

Wednesday, 24 June 2009

Irane Gonotontro Mukti Pak

Sunday, 21 June 2009

Inside the Shongshod

“Happiness is a butterfly, which when pursued, is always just beyond your grasp, but which, if you will sit down quietly, may alight upon you”

I sat there, looking at the foreign minister, dressed in her gray sari across the room, surrounded by Awami stalwarts in their penguin uniforms. My thoughts drifted to a fantasy, of stopping her in the hall, of telling her to tell to the PM not to recognize the results of the Iranian election, to stand against the violence and barbarism that the government is inflicting on our people. Our government has barred its teeth against us, the people it was charged to represent. Our soldiers have fired on us, they have aimed their guns and honor at the people they had sworn to protect. And now images of Neda, her desperate family trying in vain to save her life, are stuck in my mind forever.

I am determined to play whatever part I can here in Dhaka. It is so important for people here to know and show support for students who are being persecuted in Iran. Demonstrations in Western capitals will never have the impact that a show of support will here. I hope I can get through to people in Bangladesh that fighting American imperialism is no excuse for the kind of barbarism the government has unleashed on us. I hope I can communicate to my fellow students here that we are all in this together, that nothing, nothing can justify the killing of students, the raiding of their dorms. Tehran is Tienanmen, it is Gaza, it is so much more than a disputed election. The government is now creating the future sites for a thousand Shohid Minars. Their fight and yours has always been the same. See that, and speak out, now, while it still matters. Stand with my people, and let the world know we are not alone.

If you are in Bangladesh, read, sign, and forward this statement: http://www.petitiononline.com/deshiran/petition.html

Sunday, 14 June 2009

1979 - 2009

Friday, 12 June 2009

The sabzi is more Persian on the other side...

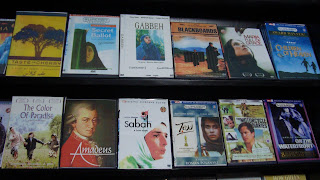

I count seven Iranian films in this one picture. Iranian films, ones I have never heard of, are available everywhere in Bangladesh. This past winter in Iran, I searched in vain to find Iranian art films by Kiarostami, Makhmalbaaf and others in Tehran's movie stores. I found a great deal that was pirated and Hollywood, and an increasing number of Hindi movies. But it was impossible, literally impossible to find our Iranian films anywhere in Tehran. I bought a copy of "Secret Ballot", an Iranian comedie about our ridiculous elections and burgeoning democracy, and Matir Moina (The Clay Bird), a film about the social fissures that gave birth to modern Bangladesh.

I never, not in my wildest dreams, imagined that the first time I would vote in an Iranian election, I would be doing it in Dhaka. The Iranian community here is small, tight knit and eccentric to the last. One gentlemen had been here for the last 35 years, sneering at the place, railing against its every nook and cranny, but somehow so in love that he learned Urdu, Sanskrit, Hindi, and (as he claimed and I refused to believe) became the first Iranian to learn to read Bengali, which he again claimed no Bengali could write without making numerous spelling mistakes at every go.

Then there was the tea magnate who had lived here for fifty years, and the petro-man and the one who imported carpets and handicrafts to Bangladesh. We all sat around eating watermelons and imported kharboozeh, arguing intensely over whether khiaar was Arabic for cucumber, or whether it was really related to ikhtiyaar and hence never originally the name of a fruit. We then proceeded to find every last word (there are about 17,000) in common between Bengali and Persian, scratching our heads over why z's became j's and s's became sh's and finally, revealing that Mumtaz Mahal was actually an Iranian from Yazd.

Thursday, 11 June 2009

Eliminate "Monga" Forever

We can set up a program on our campus to collaborate with the Freedom Foundation in Dhaka to raise awareness about and get people all over the US and Canada involved in coming up with a way to set up a sustainable rice bank system that can be financed (so it doesn't have to rely on outside funds). I am working on a grant proposal to study the rice bank system next summer, and I'll try to learn as much as I can about the process in the coming weeks.

The people solving these problems in Bangladesh are not super heroes, they are not even geniuses. They are exactly like us, no more or less capable than we are. They have just realized how much they can do while the rest us are only just opening our eyes to all this. I visited the FF headquarters today and spoke to Safi Khan, head of the organization. He is an amazing, dynamic and highly motivated Bangladeshi American who is really committed to what he is doing.

Wednesday, 10 June 2009

Rickshawalla...

CNG’s and rickshaws are out. Cost had started adding up, especially paying as I was, the shaddha chamra, the firengi price. I asked a student-looking young man for directions, for college students everywhere are part of a single international brotherhood of the young and hopeful. “You are a guest in my country, if I do not help you then I am shy to saying I am Bangladeshi,” said Mashfique, my new best friend. And so we walked for the better part of a kilometer to a ticket stand where burly men sitting behind wooden boxes shouted like it was some kind of high end auction. I hopped unceremoniously onto the accelerating footboard, for buses never stop moving in this place. I landed with a thump into a bus full of amused expressions, regained my balance, and starred out the window at the shanty towns, the sweeper women and rickshallaw traffic jams we passed by...

Jao, rickshawalla,

Stop rickshawalla,

Aste aste rickshawalla,

Dore dore rickshawalla,

You ferry my princely self around town for pennies on the dollar,

I’ll sit here and play Rudyard Kipling.

Bame, dane, eidike, oidike, ei pasha, oi pasha,

Jao rickshawalla, jao!

I only see your face when it’s time to pay,

Sometimes not even then

And then we’ll haggle over a few dimes, because haggling is chic,

Onek door, rickshawalla? The sun is making me tired,

And I left my chati home,

Because where I come from, chatis are for rainy days

And sunscreen is for sunny days, and deodorant is for sweaty days

And AC for hot days, and bottled water for

Those unpleasant thirsty seconds between when we are full

Tuesday, 9 June 2009

Laal Baaq Friends

The Laal Baaq Fort is an island of serenity in a turbulent sea of rickhsaws, smoke, vendors and bustling humanity of old

The Laal Baaq Fort is an island of serenity in a turbulent sea of rickhsaws, smoke, vendors and bustling humanity of old What followed was a Bengali conversation that took the better part of an hour. I proceeded to do a thing I have been dreaming of doing for a long time. I explained two verses of my favorite poem by Rumi, while speaking Bengali, in a Mughal fort, in the middle of

I walked on after the kind of farewell you hand people you have known for a long time. A group of little school girls, dressed in bright pink shalwar kameez, ran up to me, laughing, pointing, shouting “kamon achen?!”. “Bhalo!”, I replied as their faces lit up in astonishment as I threw in an “As’salamu alaykum” for good measure. They ran off, laughing hysterically, radiating waves of happiness, riding on the gentle breeze.

And then there was Mohsen, the young poet who wanted so badly to publish his work, but was too busy with school and kaaj and everything else to find the time. For close to another hour, we sat and talked, my mind feeling itself slowly but surely into a language no one had ever spoken to me five days ago. He turned to his best work, with tremendous pride, and again, I left his presence like I would an old friend.

Monday, 8 June 2009

First week in Dhaka

The rickshaw traffic here in Dhaka is incredible. The other day, my rickshaw fell over and spilled me into the street. Rickshawallas have a tough job, pedaling day and night, rain or shine. I can haggle with anyone and everyone, but never with a rickshawalla. Every rickshaw is the unique creation of its owner, and designs are highly individuated. 600,000 rickhsaws means this place is crowded, but the air is cleaner than I expected. I see trash in the streets, but the absence of plastic bags is notable. Almost all the waste here is biodegradable.

The Jatiyo Sangshad (National Assembly Building) designed by American architect Louis Kahn. Seeing the building in person is incredible. The lush, green paddies that surround this place, the serene concrete facades, the crisp geometric cutouts, all work to create a deeply moving aesthetic. On the other side of the street lies the Zia memorial park. The place is full in the mornings with karatekas, cricket matches, strolling families and young students craming quizzing eachother before exams. A peaceful, place, and full of life.

The Jatiyo Sangshad (National Assembly Building) designed by American architect Louis Kahn. Seeing the building in person is incredible. The lush, green paddies that surround this place, the serene concrete facades, the crisp geometric cutouts, all work to create a deeply moving aesthetic. On the other side of the street lies the Zia memorial park. The place is full in the mornings with karatekas, cricket matches, strolling families and young students craming quizzing eachother before exams. A peaceful, place, and full of life.